#90 Moments of Perception

Moments of Perception: Experimental Film in Canada

[from Goose Lane Editions catalogue]

Moments of Perception

Edited by Jim Shedden and Barbara Sternberg

352 pages

Published: November 16, 2021

Non-Fiction / Art & Architecture

ePub: 9781773102443 $19.95

Film is the art form of our times. It has formed the background of our lives, informed visual arts practices, and formed our culture’s stories, its memory.

Moments of Perception is a landmark book. The first history of twentieth and early-twenty-first-century Canadian experimental filmmaking, it maps avant-garde film across the country from the 1950s to the present day, including its contradictions and complexities.

Experimental film is political in its very existence, critical of the status quo by definition. In Canada, some of the country’s best-known artists took up the moving image as a form of artistic expression, allowing them to explore explicitly political themes. Mike Hoolboom’s exposure of the horror of AIDS, Josephine Massarella’s concern for the environment, and Joyce Wieland’s satiric look at US patriotism are just a few examples of work that contributed to social movements and provided a means to explore issues of race and gender and 2SLGBTQ+ and Indigenous identities.

Featuring a major essay on the history of the movement by Michael Zryd and profiles of key filmmakers by Stephen Broomer and editors Jim Shedden and Barbara Sternberg, Moments of Perception offers a fresh perspective on the ever-evolving history of Canada’s experimental film and moving image media arts.

#89: I AM HERE playlist

Our forthcoming exhibition, I AM HERE: Home Movies and Everyday Masterpieces, was partly inspired by the bits of wisdom embedded in popular music. Every section of the exhibition was named after a particular song. You can hear all of them, plus a few other songs that belong on the list for context, and because they're great.

The list: I Am Here - Pink

Our House - Crosby, Stills and Nash

Our House - Madness

We Are Family - Sister Sledge

Food, Glorious Food - Mark Lester, Harry Secombe, Peggy Mount & The Boys (from Oliver!)

Fight the Power - Public Enemy

Ultralight Beam - Kanye West

Happiness is a Warm Gun - The Beatles (or anything else from The Beatles/“The White Album”)

Dance to the Music - Sly and the Family Stone

My Favorite Things - Julie Andrews

My Favorite Things - John Coltrane

Let it Bleed - The Rolling Stones

Andy Warhol - David Bowie

The Angels Wanna Wear My Red Shoes - Elvis Costello and the Attractions

On the Street Where You Live - John Michael King (or Vic Damone or any other “Freddy”)

Life is a Highway - Tom Cochrane

On the Road Again - Willie Nelson

Groupie (Superstar) - Delaney & Bonnie

Superstar - The Carpenters

Superstar - Sonic Youth

Wrecking Ball - Miley Cyrus

Kodachrome - Paul Simon

So You Wanna Be a Rock ‘n Roll Star - Patti Smith

Everyday People - Sly and the Family Stone

Panorama - The Cars

Being Alive - Dean Jones (or any version - from Stephen Sondheim’s Company)

Here's the playlist if you have Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/5sIHwE2c8s7sn4UzC5ylfm?si=73c90d118ea440af

#88: Fiona Smyth

As featured in our forthcoming exhibition, I AM HERE: Home Movies and Everyday Masterpieces. A mural (and the book cover) and an imaginative timeline of the technologies of self-documentation. Both works were illustrated by Fiona Smyth . The exhibition opens April 13. https://ago.ca/agoinsider/compacting-illustration?utm_source=AGO+email+communications&utm_campaign=f61def448f-AGOinsider_February_23&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d4ab708299-f61def448f-245840197

#86: WOMAD

I worked on the last WOMAD in Toronto. I was the co-programmer of the accompanying film series, so I didn’t play a very central role, but it was fun to put my film programming skills to work at an organization that I loved, and still love, Harbourfront Centre, and for this game changing festival, one that changed who Harbourfront Centre was. It was their last year partnering with WOMAD as their own homegrown programming programming didn’t need the support and validation from the mothership anymore. Perhaps I’ll write more one day.

#85: High School Music

On this day forty years ago, December 31, 1981, I went downtown to a New Year’s Eve concert featuring Maja Bannerman, Handsome Ned and the Sidewinders and The Government. The show was at Mercer Union, an artists’ run centre that was located on Adelaide St. at the time. I didn’t know what Mercer Union was, and I didn’t know what artists’ run centres were, and I had no idea that I would have some kind of affiliation with one or more of them for most of my adult life (so far). I went with my sister, Lisa, and my friend David Keyes, and I’m sure we bought our tickets at the Record Peddler. I know the draw for me was The Government (https://open.spotify.com/track/125aikDb420xmgkNGr9fYH...), a band that defined cool downtown for me, everything I longed for in my fantasy escape from the suburbs. Handsome Ned and Maja Bannerman would become part of that fantasy in due course.

The evening was what I had hoped, though I like many great moments in my life, I have a lonely memory of it, perhaps because I had no way of actually connecting to any of the people in attendance (Lisa and David notwithstanding), without getting blotto and then doing so in a blackout. Perhaps it’s because I took enough of an opiate that night, and for my first time, that I thought maybe I was going to die. I’m sure I had a case of paranoia as I went home and got up the next day, visited my girlfriend and then went to work.

New Year’s Eve, and especially New Year’s Day, have always filled me with anxiety and loneliness, along the same lines as Labour Day, each of them being the mother of all Sundays.

I suppose I’ve had some good New Year’s Eves, but they always come double-edged. For a number of years, and a number of times in my life, I’ve held parties because it beats the alternative - going out. Hilariously, a party we held for many years where we’d invite both sober alcoholic/addicts and “normal” imbibers was intriguing to the CBC, which led to an interview on “Out in the Open” that they ran 2016, 2017 and 2018, but is still available the way things are in this era: https://www.cbc.ca/.../eat-don-t-drink-and-be-merry-an....

I don’t remember much about other high school New Years. Mostly I worked my restaurant/banquet job, and in earlier years stayed home to listen to top-whatever countdowns on the radio while my mother ate lobster.

I made a Spotify playlist (https://open.spotify.com/playlist/3daskNNDhqT6IZlpwfJueH...) recently called High School. Like most of my Spotify playlists, it’s kind of random, probably a bit too sprawling, and impenetrable to anyone but me. In this case, it’s a playlist about what I listened to in high school (1977-1982), what I fantasize I listened to in high school, songs that hadn’t been recorded yet when I was in high school, songs I fantasize about singing in the band I fantasize about being in when I was in high school, and songs that I should have listened to in high school had I been as cool as I thought I was.

It’s not complete. It’s just a momentary fantasy. 71 songs, 4 hours and 27 minutes, the length of a basement party.

Some of the choices are obvious. “Top Down” and “Picture My Face” (https://open.spotify.com/track/0zYGqo3pLiVJUYCcwrn21h...) from the first Teenage Head album: a huge amount of fun and more exciting than many of the other punk bands I was into, a band that my sister Lisa and a few of my newfound friends at Mother’s Pizza (who taught me a lot about music) could agree on. We played the hell out of the record, and compared the production quality of the singles (“better” in both cases, but less pleasing to my already DIY sensibility). We saw them at every high school performance we could get to, every Knob Hill Tavern gig they’d let us into, at Danforth Music Hall, somewhere in Stoney Creek, everywhere and anywhere.

“Days of Wine and Roses” (https://open.spotify.com/track/2inEzpdn0vqBap0YJ2eD2o...) by The Dream Syndicate came out once I was in university. That album, and handful of EPs and singles by the band, along with music by The Gun Club, The Cramps, The Blasters, Rank ‘n’ File, and the Violent Femmes, were the bands that gave me hope after, to my mind, punk, new wave (as we originally understood it) and postpunk were finished, giving way to synthpop, New Romanticism, etc., etc. These bands, and hardcore bands like the Dead Kennedys and Black Flag, were the saving grace apparently. The truth is, those bands were great, but I eventually grew to hear good things in Tears for Fears, A-Ha, Depeche Mode. I’ve come to realize that there are periods of our lives that we lock into, periods that we decide define our identity to the exclusion of everything else, and then we turn off. At least, I do or, I hope, did. Nothing beats adolescence for carving out one’s identity, but I am trying hard to call me on my own bullshit, even while I sentimentalize it!

When I have the fantasy that I had a band in high school, one possible version of it involves showing up to the Battle of the Bands and we’re The Dream Syndicate, a band that is not punk but is so punk, a band that has to appeal to anyone into 1970s hard rock, from Neil Young and Crazy Horse to the alt protopunk variants like the Velvet Underground and The Stooges. That’s my band. One of them.

The Stooges’s “Not Right” (https://open.spotify.com/track/6ghf1333jb7cJ9sQCgMRWl...) is one of a dozen or so songs by the band that were always heavier and more exciting than most punk bands. That was part of the musical experience of the time for me. I loved everything New that was happening during that great period in music (and film, art, literature, DIY-ness), but it was impossible to disregard the greatness of what had gone before, what wouldn’t have been on our 1050 CHUM radar screens growing up, but was happening parallel to all that other greatness.

I was too cool to be into Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, but had a song like “Beggin’” appeared by some new band out of the blue, I’m pretty sure my ears and my brain could not have resisted: https://open.spotify.com/track/7wVQgvVVX4penHEGrF5eCL...

Like almost all of my high school “discoveries” I found that my friend Kim was already into them. Actually I took my cue first from Jim Morrison, because I discovered that The Doors opened for them at the Whiskey a Go Go or some such LA place. The Doors were still cool to me, even though they were profoundly uncool by my New Wave standards. I still like The Doors, but I still love Love. I am almost shocked every time I play their music, from their garage rock classic 7 & 7 Is (https://open.spotify.com/track/0OJnkHGtb0kbUiKrboCuJg...) to Alone Again Or (https://open.spotify.com/track/1XuccRABkfUVB4FjSVhjL1...), a song so astonishingly beautiful to my 17 year old self (and my 58 year old self). I am convinced the first few songs I heard were all from the Johnny Cash greatest albums that came out in 1965 and included the mariachi-infused “Ring of Fire” and “It Ain’t Me Babe”; years later an (arguably) mariachi-infused “Alone Again Or” would become a huge favourite, played over and over again on vinyl, on tape and now online. I think I bought most of my Love records at Peter Dunn’s Vinyl Museum, but at A & A’s Yonge St. as well I’m sure (hello Kim, hello Lisa). I am tempted to go on and on about Love and I did, back in 2007 near the beginning of my Facebook Group, 1000 Songs, followed by a conversation with some of my favourite people: Alan Zweig, Rick Campbell, Gary Westwood, and Steve Winwood. https://www.facebook.com/notes/1000-songs/song-57-alone-again-or/10150206403561451/ PS: Scott Walker's "Seventh Seal", an inarguably mariachi-infused psych/crooner gem, hit me as strong as Cash and Love. Too much to say here.

A big part of my high school experience consisted of going downtown to bars like The Beverley (my favourite), the Spadina Hotel (Cabana Room mainly), and Start Dancin' (not a bar) and others to hear bands like the Rent Boys (https://open.spotify.com/track/2RYbxnAVvKEaUak6i1rVMn...), the Sturm Group, the Rheostatics, the Dave Howard Singers, Fifth Column, and so forth. The music I heard then, and the connections I made still live with me, even if sometimes very tenuously.

I’m not sure if I listened to the Spencer Davis Group when I was in high school, but I should have. This song, I’m a Man, is pure pleasure whether it’s this original (https://open.spotify.com/track/3FBQJqRo62hW0RvGoJXWdB...), or Bob Seger or Chicago. Steve Winwood is a reminder that it was possible to be musically accomplished as a young teenager. Apparently you have to work at it harder than I did.

“Nice ‘n’ Sleazy” (https://open.spotify.com/track/2CeBK22RiNWepnaCs0yHPb...) was one of the first punk songs that my sister owned, and maybe the first either of us had on a picture sleeve. The Stranglers are a band that still sound fresh and exciting to me. My fantasy band would play “Golden Brown” and “Hangin’ Around” (https://open.spotify.com/track/4OvQsAObGMF3dpkCV6DZzb...), as well as their version of “Walk on By” (https://open.spotify.com/track/468OjJdSYyN77e1tYj4O6Y...).

Richard Hell and the Voidoids were like the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, and Patti Smith to me: “HOLY SHIT!” That anarchic energy cut through everything for me, and still does, though today its part nostalgia, and part genuinely reminding to cut the shit and focus. I love “Blank Generation” (https://open.spotify.com/track/5OGfBbWmRRkDiZiJbu5WIr...) and their version of John Fogery’s “Walking on the Water” (https://open.spotify.com/track/4qbhCFHUmMMXnP09MKMcZP...).

Which reminds me: CCR have never grown tired for me.

And did I mention Neil Young and Crazy Horse? It was so exciting that Rust Never Sleeps came out while we were in high school. It seemed impossible that my generation could have an album as earth-shattering as Everybody Knows this is Nowhere or After the Goldrush, but time has proven that, to me at least, Rust and Live Rust are two supremely high points in their career.

Sometimes I know it’s just nostalgia. So Some Girls is my “favourite Rolling Stones” album, but I can’t sustain that position. Exile, Sticky Fingers, and Let it Bleed are obviously “better” and each is also “my favourite".

I really must be going. Happy new year!

Rent Boys Inc · Song · 1982

33Alan Zweig, James Anderson and 31 others

8 Comments

Like

Comment

Share

8 Comments

Lisa SheddenHappy New Year, Jim. I miss spending New Year’s Eve with you.

1

Like

· Reply

· 19h

Aldona SatterthwaiteHappy New Year, Jim. As I'm mostly an introvert, I love spending New Year's Eve by myself. I've never liked New Year's Eve parties--everyone so desperate to have a good time and all that false bonhomie. Nuh-uh. Instead, I make myself a really fabulous dinner, drink a little Prosecco (or champagne, if I'm feeling fancy), and usually watch all five hours of the BBCs production of Pride and Prejudice (the one with Colin Firth and Jennifer Ehle). This year, I might check out Get Back, the Beatles' documentary on Disney+, instead. Cheers!

2

Like

· Reply

· 19h

Kerry DooleFine choices!

1

Like

· Reply

· 18h

Rick CampbellHey, Jim that’s quite a piece! Are you sure it wasn’t NYE 1980? Andrew told me that their opening gig for XTC at the Concert Hall was The Government’s last gig and that was October, 1980. I know because I moved to the UK the next day.

Like

· Reply

· 15h

Jim SheddenRick Campbell I hate to disagree with Andrew JP about his own band, but I was at several shows when I was in grade 13, which was 1981-82. I have street posters to do it, not to mention an interview with Robert Stewart in one of my zines that took place in 1982 and the band was still together, but I guess that must have been the end.

Like

· Reply

· 13h

Rick CampbellJim Shedden Okay. Maybe they broke up more than once! Billy Bryans wasn’t their first drummer so…

Like

· Reply

· 12h

Jim SheddenRick Campbell Its possible that a show I saw of theirs at the Palais Royale, on September 18, 1981 (my birthday) was the first show with Billy Bryans. I believe he also played with every band that night.

1

Like

· Reply

· 3h

Active

Write a reply…

Nick Smashthanks jim. this very much echoes my own experiences.

Like

#84: New Year’s Eve Parties as heard on CBC

#83: Incomplete

And what have you done?

Thoughts on incompleteness in lieu of New Year’s Eve resolutions.

I hope you’re having a great holiday. I am, though I am somewhat melancholy. It may be the cloudy skies but I think it’s more than that. I feel this overwhelming sense of incompleteness. That can be tied to the number of loose ends in my life right now, projects in limbo, and projects at the mercy of a worldwide pandemic. It might just be my neurotic personality, but I think it’s more than that as well. And what if it isn’t? My experience of the world right now can only be described as “incomplete”. Doesn’t really matter what caused it. Perhaps I have a combination of imposter syndrome, anxiety, and FOMO, all of it made hyperbad with coronaphobia.

According to my Myers-Briggs indicator results time and again for almost 30 years, I am an ISTJ, which means, among other things that I thrive on closure. That can be a good thing, of course, but creative work thrives on open loops. One has to be patient, adventurous, uncompromising, and yet determined enough to bring the project to fruition when it’s due, or when it’s ready. Open loops are one thing; spinning one’s wheels incessantly is another. And one needs to be wise enough to walk away or put things on ice when the universe just won’t budge.

According to Myers-Briggs language, “People with the Judging preference want things to be neat, orderly and established. The Perceiving preference wants things to be flexible and spontaneous. Judgers want things settled, Perceivers want thing open-ended.” I have learned, with this particular preference of mine, to work against preference, to embrace open loops, incompleteness.

When I finish something, even if I downright hate it at the time, it almost always ages well, for the simple fact of being finished and out in the world. The most infantile of fanzines, quaint posters for quaint events, awkward essays and articles, homely books, and amateur videos - these artifacts become less embarrassing over time and, instead, are reassuring stakes in the ground. Fortunately I have enough of these to battle the entropy of my decaying memory. They remind me, too, to persevere, to get to the finish line.

I’m not just talking here about my various projects, but also books read and not read, films and plays seen and not seen, travel ambitions, purging of stuff, photos scanned and not scanned, digital file management, recipes tried, repairs and renovations, 12 steps taken, community and charitable commitments, and family obligations.

Another part of me refutes this need for tangible completeness. I realize that my character, my imagination, and my overall consciousness is shaped by the journey, the overlapping experiences. This is made abundantly clear by travel. These days when we travel we create photographs and video, buy objects that help us remember the stops along the way, like this Pendleton shirt that I’m wearing is a marker of a brief time in Portland, Oregon. But even my travel experiences when I created or collected very little documentation, shaped my life enormously: I think of camping trips and trips to Montreal, Cape Cod with my parents and sisters; my first trip to Europe - Budapest, 1991; various trips when I was at Bruce Mau that are primarily only marked in my mind (eg, Copenhagen, Rotterdam/The Netherlands, Vienna, Ghent, Paris, Essen, Basel/Weil am Rhein, Atlanta/Cartersville, LA, SF, Chicago, Orlando, and a hundred trips to New York). But in some ways each trip was an act of completion, just as each household chore is an act of completion.

A few Incompletions from the past disturb me to varying degrees:

My film, Music Swims Back to Me, that went off the rails during the pandemic. It’s possible that we will find a way to finish it, but I am in mourning to tell you the truth. The stars are not aligned it seems.

Travelling to Italy, an ambition that goes back 35 years with me, and that I haven’t been able to make happen. The pandemic negated the last such plan (we were supposed to go in May, 2020). I think any significant trip to Europe right now would allow me to let go of the Italy ambition, because I’ve added to it the desire to go to Norway, Finland, Sweden, back to Denmark, maybe Iceland, return to Belgium and the Netherlands, more UK and Ireland, more Germany, and on it goes.

A book I started writing on the filmmaker Dziga Vertov (primarily Man with a Movie Camera, in the early 90s. I think I got about 40,000 words or so into it and then abandoned it. I haven’t had the courage to just throw the manuscript away, but there is no book there.

My website jimsehdden.com is a bit derelict. I know nobody looks at it but when I was updating Linkedin and the profile info on all my social media sites, I thought that it was ridiculous that I didn’t have my own site that reflects my life, projects, writing, and media files. It’s underway, but kind of pathetic.

My 12 step program. I’m clean and sober, but during the pandemic (of maybe even before it) I just drifted away from the fellowship and the structure that is the reason I’m alive today. I have to find my way back.

Never finishing Middlemarch, Bleak House, Infinite Jest, anything by Pynchon,

Walking out of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles when it was shown at the AGO around the time I started working there. It was a sunny Sunday afternoon and I thought I was going to die of boredom. Since I have seen several Akerman films that I quite like, and since this is highly regarded by various people that i respect, I’m pretty sure I was just in a pissy mood that day, and that it’s time to Complete watching the film.

Same goes for Tarkovsky’s Andrei Roublev.

Learning another language. I sleepwalked through French in high school, always getting 80s and 90s, but retaining nothing. I wanted to rectify that, and I’ve had ambitions to learn German and Italian. I did take a few Italian classes with a bunch of friends in 1992 or thereabouts. But I abandoned it. I feel like I still need to master another language even though it will now be harder than if I had done so in my 20s or 30s.

Learning to play piano properly. Learning the guitar. Learning to sing.

Becoming a better cook again.

Learning InDesign again. I understood it enough to lay out simple books years ago. When I look at it now I haven’t a clue how to even start. I need to have that skill in my toolkit again.

Reconnecting with friends who have disappeared from my life for one reason or another,

Is it my new year’s resolution to dive back into some of all of these abandoned dreams?

Maybe. But this year I will be launching a major exhibition (I AM HERE: Home Movies and Everyday Masterpieces), with an ambitious accompanying book, and I will produce at least 8 other publications for the AGO. I will be working on another exhibition that opens next December that could not be more exciting to me personally (but that’s all I can say right now). I will be continuing to disseminate and promote my book, Moments of Perception: Experimental Film in Canada (ed. with Barbara Sternberg, and major contributions by Stephan Broomer and Mike Zryd). I will independently publish a book on the painter Mashel Teitelbaum, and help produce a book on Inuit and Sámi culture. I’m going to continue working on improving my neurochemical and mental health. I’m going to make some unexciting but necessary home improvements. I’m going to travel to NY and maybe SF again…. I hope. I’m starting a music salon with Meredith and Shellie (February? At the Dominion tavern). I’m going to get new glasses, orthotics, work boots. I’m going to the dentist. I’m going to spend time with my father and sister. I’m going to get my recovery program back on track. So maybe I’m not going to learn German

#82: Dave Hickey's Air Guitar

Dave Hickey R.I.P. Hickey is the third cultural critic to die this month who changed my way of thinking. In Hickey's case, his collection of essays, Air Guitar, blew my mind when it needed to be blown. I barely knew his work before Air Guitar, but I read the book when it came out. I was working on a film about Stan Brakhage, and Hickey had a cantankerous, dismissive piece about Warhol and Brakhage films that I found strangely appealing. I didn't agree with it but I still found Hickey's position liberating. There was something energizing about his insistence on speaking personally and honestly about his subjects, about his very active crossing of boundaries, and how that meant a series of "essays on art & democracy", including reflections on Hank WIlliams, Liberace, Cezanne, Perry Mason, LSD, Flaubert, Chet Baker, Lady Godiva, Siegfried and Roy... well, you get the picture. Hickey allowed me to get out of my critical and aesthetic rut.

#81: The Beatles: An Illustrated Record

I think it’s safe to say that this book changed my life as much as any gift. It turns out my musical sensibility was informed as much by reading about it music as it was by listening to it.

For example, for a number of years I was reading rock magazine articles about Lou Reed, Patti Smith, Television, the NY Dolls, and Richard Hell before I heard any of them. By the time I actually heard them, I was already sold. Similarly with the Beatles, by the time I got this book (1975) how much Beatles music had I heard? Barely any. I had a few solo records by the Wings and Lennon, and some random singles like “Photograph”, but in terms of actual Beatles songs I’m pretty sure it was “She Loves You” (we had the single), “All You Need is Love” (the theme song for Family Finder!), “Good Day Sunshine,” “Yellow Submarine”, “Hey Jude”, “Let it Be”, and maybe 3 or 4 more songs. Honestly.

But I was pretty sure the Beatles were my favourite band. This book sealed the deal, even before I had my copies of the blue and red anthologies. Combined, the book and the red and blue anthologies got me through Grade 7 & 8, while punk and new wave were waiting to happen.

I remember the book basically being a comprehensive annotated discography or Beatles records, along with pretty great photographs, press clippings, and quotations. I remember the images with the Maharashi Mahesh Yogi pretty clearly, not to mention the Two Virgins album cover (I was 12!). I also remember that it was pretty critical of the solo albums, especially All Things Must Pass. The latter is considered one of the high achievements of the Beatles solo universe and, over time, I have become more and more partial to the solo records as a whole. They may not be Revolver or Sgt. Pepper’s or The Beatles, but I suspect “the next Beatles album” that many fans wanted to see happen, might have been a dreadful clusterfuck. Maybe. it seems clear to me that at least Jean, Paul and George had solo work to do that would not have been supported by the other Beatles.

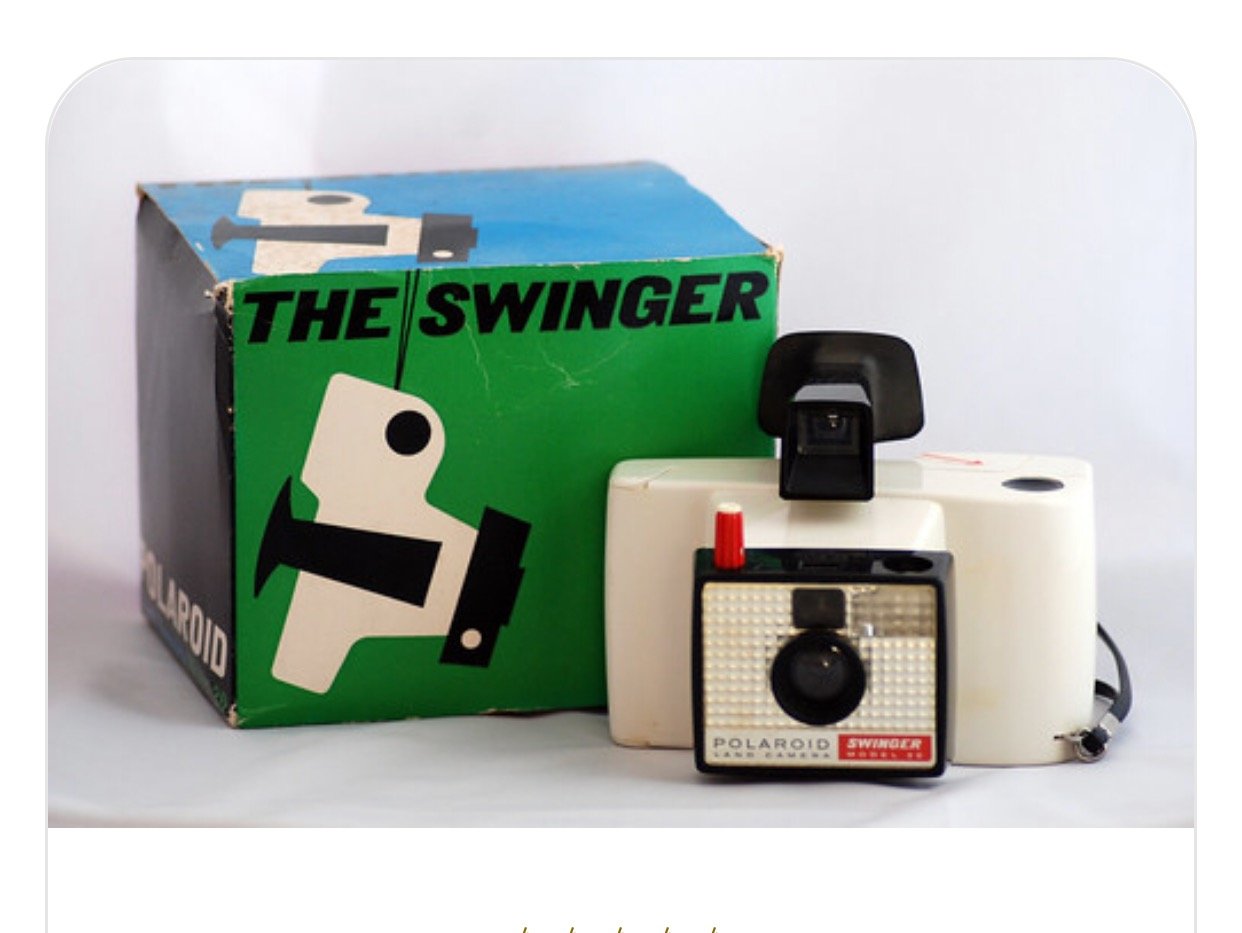

Anyhow, many wonderful hours and years with this book. Thanks mom (R.I.P.) and dad. And thanks for the Polaroid Swinger too.

#80: The Polaroid Swinger

For Christmas of 1972 I got a Polaroid Swinger camera. It was my first camera and it was one of my most memorable gifts ever.

However, the word “memorable” is open for discussion. The model I’m showing here was too funky looking to resist, but I think it was discontinued in 1970. I think there were spinoffs of the original Swinger, and that’s what I must have had. Perhaps it was the “Super Swinger,” which was apparently released in 1972 and sounds like my camera. The pictures were tiny, black and white, and expensive. I seem to remember that an 8-pack costs something like $20, 50 years ago! I was nine years old and had no income.

My memory also tells me that I got the camera in 1974, even though it can’t be.

I LOVED this camera. I still have a handful of photos I took with it. My love of taking pictures (there is no term for that outside of shutter bug) went dormant for five or six years after that when I bought a Nikon EM, and others that followed, until I settled on my iPhone camera like everyone else.

PS: since I was about 17, I have been saying to my various families that we should give up gifts and only make charitable donations this time of year. I still feel nauseous at how much conspicuous consumption and self-centred expectation dominate our souls this time of year. Did I get it? Is it the right size? Is my gift to them better than theirs to me? Is that good or bad? When can I return it? Is it fake? Is it generic? Is it a regift? Who gives gift cards anyway? Who gives cash anyway (actually, no one says that)? A panettone again?

All of my liberal guilt and disgust aside, though, I realize that a) I really like giving people gifts and b) a number of gifts have really changed my life, sometimes in small ways and sometimes in large ways, when you get right down to it. The Swinger was one of them.

#79: Jim at 14 (years of sobriety)

Jim at 14

October 23, 2021

I have been clean and sober since October 23, 2007. I have not had an alcoholic beverage or an unprescribed drug since that date.

Since I don’t even crave alcohol or drugs today, it seems like an eternity. But since I know how easily that can change, how my addiction can turn on me, it also seems like only yesterday.

From a very young age when I had tiny sips of booze at Christmas, I fell in love with it and obsessed it all year round. When I was 12, though, I began reading all kinds of books about addiction and pop psychology. A few years before that my father went to George Brown College to study to be an addictions counsellor, something that intrigued him after his own path to sobriety began at the former Donwood Institute. He didn’t follow through with that, but I was afforded a library on the various facets of addiction and sobriety as the world understood those concepts in the mid-1970s. On top of that, I was attracted to novels (what we would now call YA literature) like Tuned Out, mostly drug and addiction scare literature, and then books like Sara T, Portrait of an Alcoholic (also an after school special). And, for a few years there, my musical hero was Randy Bachman, a Mormon and therefore straightedge.

The point of all this is that early education on alcoholism and addiction did not temper my excessive alcohol and drug use. I had the negative and positive example of my father and various people he met at Donwood. I had all those books and pamphlets and novels and short stories and films and TV shows, not to mention the example of my childhood musical hero Randy Bachman. Through grades 7 and 8 I had decided there was no reason to ever drink or drug.

When I was 14, in grade nine, I started getting alcohol here and there, at first to fit in with people I wanted to befriend, and then because I loved the feeling of oblivion, letting go of me and my fears. Within about a year, however, I discovered that alcohol (and drugs) allowed me to cope with life even when I wasn’t partying. It helped me ask girls out on dates, it helped me in social situations where others weren’t partying, it accompanied me at practically every live performance (and I went to scads and scads of them), through pre-drinking, sneaking out at intermission to go to, say, to The Morrissey when I was watching a show at the Concert Hall, and by sneaking alcohol into venues in craftier and craftier ways. I even occasionally drank at movies, eventually needing the sedative effect to keep me grounded. I also took all manner of drugs - hash, mushrooms, LSD, but mainly pills, uppers, downers, and all-arounders. Alcohol was my drug of choice but if you took it away, I’d have used more of those pills, more regularly. I believe I am an addict with a preference for alcohol, but I don’t believe, at base, that I have a different affliction than someone addicted to crack or opiates (when did we start saying opioids?)

When I was 18 I started suffering consequences, including troubles with the law, but at this point and right until the end of my drinking, it was all about getting away with it, because nothing mattered more than getting out of myself. I remember when I was waiting for trial, my father, who was supportive throughout, pleaded with me not to go into any bars until I was free and clear. I was underage after all and there was no reason to throw gasoline on fire. I agreed with my father, and then that night I went to the Jolly Miller with my sister. This is not a bar I had ever been to, but the opportunity to have another night of drinking despite my father asking me stay out of trouble till my trial, on and despite my agreement with him, was too great. I went to the bar, got drunk, and got into an outrageous argument with the bouncer’s girlfriend. For some reason, the bouncer had to call the cops. They weren’t after me, but I was looking for trouble.

When I was 20 years old, after an out of control weekend drinking with a friend in Peterborough, I woke up with the worst possible shakes. We were at his parents house and there was no possibility of having a drink. I also realized that I had lost my glasses, the beginning of an expensive pattern that I continued right until my last relapse (I hope) 14 years ago. In Peterborough it meant insanely wandering around the whole city and Trent campus looking for my glasses. We never found them. I swore off alcohol forever, got on the bus to Toronto because I was working in the comic book store that night. On the way to my shift, I picked up a 24, and took the edge off throughout my shift.

I spent the next 24 years meaning to quit, sometimes quitting for 2 weeks, 6 months, and once even 15 months. But each time I reserved my right to drink again, which is exactly what I did. It was killing me, it was damaging the person that I wanted to be, but drinking was too compelling. And when it stopped being compelling, I still couldn’t stop, even though I wanted desperately to quit. I needed to drink to deal with the effects of my drinking. I would drink, or take a sleeping pill, to get rid of the shakes. I would be so thankful when the shakes had passed, I was so happy to be alive that I found myself forever swearing off again… until around 4pm, and then I would end up in a local dive bar just for one or two (that would turn into 8 or so), then to a LCBO to make sure I could maintain the inebriated equilibrium, only to repeat the cycle the next day. My whole life was like this quote from Dorothy Parker’s “Big Blonde”:

“Mrs. Morse had been drinking all afternoon; while she dressed to go out, she felt herself rising pleasurably from drowsiness to high spirits. But as she came out into the street the effects of the whisky deserted her completely, and she was filled with a slow, grinding wretchedness so horrible that she stood swaying on the pavement, unable for a moment to move forward.”

In the spring of 2007, I managed to back myself into a corner pretty badly, and I had to agree to get sober. I found myself drifting from private counselling to a daytox program to finding myself drunk and, to top it all off, behaviour that increasingly suggested I was manic-depressive (a term I prefer to bipolar disorder). The counsellor at the daytox program proved to be a life saver, eventually persuading me to attend recovery meetings. I eventually ended up at Homewood Psychiatric Hospital in Guelph. Homewood was a civilized but firm institution that allowed me to dry out, to start getting honest with myself and others, to understanding that the only solution they had was to get us on a lifelong pattern of 12 Step meetings and, as a bit of a sidebar, allowing me quality time with a psychiatrist where she put me on lithium carbonate, which I take to this date. It regulates mental/emotional cycles and contributes to my sobriety: my alcoholism wasn’t caused by my manic-depression, but they feed each other.

It’s interesting that I can take pills for manic-depression, my neurological disorder, achy muscles, sunlight deprivation, and other issues that come and go. For my alcoholism there are no such pills and, though I applaud the various scientists working on the case, I do wonder if they will ever succeed. So far there have been pills that make you violently ill if you drink (antabuse), naltrexone to eliminate the pleasure and reduce the cravings, campral for withdrawal symptoms, and a handful of others. These are not so compelling sounding. For a drug to be effective in “curing” my alcoholism, it would have to take away my self-centeredness, my fear, and my resentments. Addicts don’t have a monopoly on these character defects but, for me, when they are inflamed, there is always a danger that I might drink, drug and fall into a melodramatic, melancholic, poor-me (pour me a drink), self-flagellating, stupor.

So part of my recovery has been doing the things I have to keep those defects at bay. If you know me, you might wonder if that’s working, but I’m pretty sure it is. I’m pretty sure the combination of things that I am doing in that regard (as well as taking lithium) has made me more chill (or at least neutral). I am not prone to disappointment or anger, but I’m also less prone to excitement and anticipation. Something may be lost in tamping down these emotions, but I can’t afford to fall off the wagon. I’m pretty sure I might die.

The most important part of my recovery though, has been the sense of community that I’ve found in fellow alcoholics and addicts, the idea that I’m “no longer alone”. That idea has had many meanings over the years, but it is the constant, and I fully expect it to be the core of my recovery as I go forward.

(PS: I have the occasional beef with the way some people interpret 12 step groups, but, rest assured, I have been an anti-authoritarian atheist the whole time I’ve been involved and it has not been a problem. I have been allowed to get and stay sober, be part of the community, do service on every level, and voice my opinion on all matters.)

#78 Labour Day (The Mother of all Sundays, the worst possible Sunday Doom Syndrome)

Labour Day.

A virtual Sunday. The most virtual Sundays of all of the Holidays.

Everything I’ve never accomplished comes back to haunt me. Every flawed project, and every disaster comes back to haunt me.

Everything I fear about the future - work, health, family, friends - gives me anxiety. I jump to conclusions all over the place. I am overwhelmed by what I need to do, and what might happen to me. I am full of worry and stress about the consequences of my actions. I think I can’t cope.

I’m tense and nervous and can’t relax.

Low-grade existential dread. I read somewhere that someone described as wondering if she had been productive enough AND whether I had relaxed enough on the weekend/long weekend/holiday/vacation. The answer is “no” to both questions.

This is the burnout syndrome common to the millennial generation, but I’m almost 58. Damn: more anxiety. Have I accomplished enough? Have I been a good father, friend, husband, son, employee? I can’t bear to think about it.

Whether I sleep any other night of the week, I am typically up all night on Fridays, the pressure to “relax” and “let go of the week” too much, so the occasion to do so backfires. Sunday is the other night I can’t generally sleep. And then it’s Sunday: did I get enough done? Did I relax enough? Can I fix everything, finish everything, learn everything,, and do and be everything?

This is ridiculous, but as tangible as can be. This feeling, and “the Sunday Doom Syndrome” in general goes back to when I was 11 and beginning grade 7 at Henry Hudson Senior Public School (still there). I don’t think think there’s much that can actually be done about it, aside from the mindfulness-meditation-yoga-gratitude-YouTube videos-CBD gummies lazy susan of modern non-pharmaceutical treatments for the range of conditions that ail and define us: PTSD, ADHD, OCD, borderline personality disorder, bipolar affective disorder, paranoia, anxiety disorders, schizoaffective disorder, alcoholism and addiction, eating disorders, and on it goes.

Those are good things and, in the form of the AA steps have been largely responsible for saving my ass. The AA steps can be summed up as Surrender, Hope, Commitment, Honesty, Truth (Disclosure?), Willingness, Humility, Reflection, Amendment, Vigilance, Attunement, (Meditation/Mindfulness/Prayer), Service. Something like that. When I have been actively practicing the steps, I swear I’ve been less tormented by Sunday Doom as I am today.

So the answer is obvious.

An end to the current phase of capitalism would be a start. Not that long ago, when I would have been a coal miner in Scotland or in Quebec, my days would have been longer, entirely toxic, and with death perpetually at the door. My only respite would be a Sunday that would revolve around church, its own form of torture for me, despite, I’m sure, momentary blasts of pressure from being part of the congregation, and the joy of music that comes with that. But, a few hours later, back in the mine. We’ve made a tiny bit of progress but, given the massive amount of wealth we’ve managed to generate, we seem stuck with the current model of 40 hours (or much more if you’re “management”), with relatively little time actually to exist as homo ludens (playing-humans) as opposed to home sapiens (thinking-humans or homo ergaster, working-humans).

I can’t actually abolish capitalism, or even postindustrial capitalism or whatever you want to call this strange “wonderland”, which is too bad.

I am stuck then with that lazy susan, starting with acceptance, and then maybe a mix of gratitude and meditation, if that can be separated from rumination. And then - action. Like, why I am I writing this and not reading/ Or at a film? Or meeting with like-minded souls in AA? Or getting in touch with this person and that person and so forth? Or playing with Meredith’s cat, Bob Fosse? Or maybe organizing the basement (which I have turned into a creative activity in the past). Or perusing the archives at the TPL? Or wandering through some Toronto park? Or, perhaps (and only perhaps), cooking, but that activity is so full of anxiety and negative feelings, that I’m not sure I can move it back to where it might be helpful for some time.

Otherwise I am simply listening to Nick Cave and hoping that something transformational will come from it.

#77: Stan Brakhage and Ronald Johnson in Conversation (1996)

I post this issue of the Chicago Review here because there is a discussion between the late Stan Brakhage and the late poet (from Topeka, Kansas), in Boulder, Colorado in 1996. The interview was conducted by me -such that it needed “conducting” - for the purpose of inclusion in my 1998 documentary, Brakhage. Like much of what I recorded during that time, it wasn’t usable at all in my introduction to Stan, but it made for good for print transcription. R.I.P. Stan and Ronald. http://docshare01.docshare.tips/files/14733/147330535.pdf

#76: The Avenue Open Kitchen

50 Lunches

Lunch #2: Avenue Open Kitchen

7 Camden St, Toronto, ON M5V 1V2

(416) 504-7131

I love diners. Greasy spoons of the "cheeseburger, cheeseburger" variety. DIners and their close cousins NY delis, "dining rooms," "family restaurants", fish and chip joints, and value steakhouses.. Downtown Toronto 25 years used to be teeming with them: everything from the Lite Bite (Queen & Spadina - my favorite), the Stem, Murray's, Switzer's, The Bagel, The Varsity, The New Varsity (another favorite), Student's, The Grad Restaurant, Fran's various locations, Al's (Queen & Duncan), Nick's (Queen & Duncan - am I right about these two?), Lindy's, the Tulip, Senior's, Mars, Kos, the Patrician, the Skyline, Sunset (it used to be just one location!), the Golden Gate/GOOF, Elvis Restaurant. They haven’t completely disappeared, but they’re getting close.

The Avenue Open Kitchen opened in 1983. I was introduced to it in early 1999 by by friend Dan Donaldson when I was working at Bruce Mau Design. I loved like I’ve loved almost no other restaurant and, as it turns out, from 1999 to 2010, when I left Bruce Mau Design, I ate there at least 1000 times. That sounds insane, even impossible, but it’s only an average of twice a week over ten years. Even counting for the years where we barely left the studio, and even counting for all the time I spent travelling, it’s still probably 1000 visits.

It’s tiny and cramped and comfortable, a little bit like some diners in New York, only a little more casual. As for the food, they make a great breakfast and they’re excellent with the basics - smoked meat, club sandwich, etc. - but I tend to get the entrees: blade or prime rib roast; shepherd’s pie; macaroni and cheese; beefaroni; pork chops; and other things along those lines.

I am very comfortable in such places and seek them out wherever I am. I believe that 900 of my 1000 visits have been alone, and that is almost my preference. I do always run into certain characters there. For example, I suspect architect John Shnier has been to the Avenue even more times than I have and, when he he lived and worked in the area, the same was true of Jason Halter.

If you’re willing to go to lunch with me, I will always be happy to go to the Avenue.

(As far as this list is concerned, this is the farthest from the AGO that we will venture.)

#75: Listening in Depth

Memo to Alan Zweig: I’ve been meaning to mention that this was one of the first albums I ever heard it. It was part of a tiny eclectic collection we had around 1967 when I was three or four, and that ranged from Johnny Cash to Bert Kaempfert. I have fond memories of any and every record from back then but especially this classic of parallel 60s listening. My sister retrieved this from my father’s house, and I was surprised/not surprised that there wasn’t a scratch on it: we were most careful to be on our high-fidelity best when playing it. Though I was most enchanted by the Sounds in Motion collage when I was young, I remember pulling it out of retirement when I was a teenager, to discover that my earliest listening experiences included Stravinsky, Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim, Bartok, and Duke Ellington, alongside Percy Faith, Johnny Mathis, and Polly Bergen. I look forward to seeing you soon.

#74: Beans/Kenesatake Resistance

A film I love today #13. #afilmilovetoday Thus far, each film I've written on has had a link to a free online source for the whole film. I'm breaking that pattern with the first film I've seen a movie theatre since February, 2020, Beans. Beans is a 2020 Canadian drama film directed by Mohawk filmmaker Tracey Deer. I only identify her as Mohawk because it's clear that the content is somewhat autobiographical, looking at it does through the 1990 Oka Crisis, or Kenesatake Resistance. Deer lived through this as a child, thus informing the experience of the lead character, Tekehentahkhwa (nicknamed "Beans").

This isn't the place for reviews or the like, though it is tempting to write the like. I'll just say that I loved everything about this film, including the fact that it made me think about how much my own take on the Oka crisis has evolved, especially in recent years. At the time, I was I was just finishing my M.A. in Political Science, where I had a heavily Marxist worldview. I was beginning my (short-lived) career as a professional film programmer, and found myself at the Montreal Film Festival near the end of the standoff/crisis (both inadequate terms). I considered myself "with" the Mohawks, and against Bourassa (so much so), Mulroney, the RCMP, the Quebec provincial policy, and the armed forces, and the needs of bloody golfers. But, aside from thinking it was a miracle that I made it to and from Montreal without any aftershock from the bridge closures, I didn't really connect this to my life, my existence as a "Canadian". It still seemed like an isolated incident, and not one only understood as part of "Canadian" history, which is closer to where I'm at today.

I think at the time I was probably fixated on the history of the Mohawk people and the Wyandot (Huron) people, and their relationship to the Jesuits, and all that. The history is long, complicated hard-to-believe.

I think it's safe to say that, despite my obliviousness at the time, this was where my understanding of Canadian history as fundamentally an act of domination by Europeans against the indigenous populations, began. The lights were turned on, and then up during the Canada 150 "celebrations" that were impossible to celebrate, without qualification after qualification (as the AGO's show Every.Now.Then demonstrated powerfully).

The Kenesatake Resistance made evident to European settlers like myself the nature of the conflict between the Mohawks of Kanehsatake and the Canadian government, and the had lives and violent existence the Mohawks continued to suffer. It made evident the complete failure of the political system, and the deep racism in Canadian society. Beans was so powerful for in that it found a way to go back to these facts, and back to the lived violence of Mohawk people, in ways that (because of empathy? creativity?) might just reawaken inquiry, demands for justice, and effective action.

#73: Jim Shedden and Bruce Elder discuss "Brakhage in Toronto"

Recorded in Toronto, December 1, 2019.

Jim Shedden: I found this quite horrific poster — I guess Kate did it, maybe Paul — where we did a double bill, I guess probably for Halloween, with David Lynch’s The Grandmother and The Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes. That could not have been the first. But you know what there was though — he came to town and he did a screening at Ryerson and a screening at the Funnel.

Bruce Elder: Yes.

S: And I went to both of those screenings. And that was that. And that was when he met Marilyn.

E: Yes, that’s right. And that was shortly after Stan and I had become — when Stan acknowledged me as a colleague. It was an interesting relation, up to that point. I first met Stan in peculiar circumstances, and I think it’s worth describing these peculiar circumstances, because in a certain sense, our first encounter established the cast of our relationship. Or it provided some of the intellectual underpinnings of that relationship, because, as I alluded to a moment ago, at first our relationship was very formal and professional, if you will. I was a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Toronto, and not long after I did my comprehensive examinations, the graduate program director convened a meeting of all of the graduate students in the department. In those days you had those kind of poster-board flip charts, and he had a prepared set of flip charts showing how many students there were in top-drawer universities in North American enrolled in PhD programs, how many retirements they expected over the next several years, what enrolments they were expecting over the next several years in universities, et cetera. The story was that none of you have a chance of getting a job. That’s basically what you’re looking at.

S: It’s amazing that things got so much worse, and they got less honest. At least then they told you the truth. I had so many friends with PhDs who were, like, suddenly shocked.

E: [Laughing] Yes, that is a huge change. But I was not from a wealthy family, I was from a hardscrabble family, and there was not the same level of funding for graduate students that there is now. One of the things I found — Cathy found actually — going through the file folders was the offer for the graduate assistantship that I would get and how much they would pay me. I had even forgotten that they were prepared to pay, but there wasn’t the same level of funding that there is now. And the idea of years with no income and facing tuition and living expenses and racking up a huge debt and then not finding an academic position seemed kind of preposterous. It didn’t seem something that I could afford to do, simply as that. So, I thought what might I do with my life — moreover, at the time, I was already publishing poetry, and that was certainly what I knew I wanted the focus of my life to be. I wanted to be a writer, a poet, and so I realized I was facing the question that all creative people face, “How do I manage to pay the bills? How do I keep the wolf away from the door?” There’s no way that publishing poetry is going to pay the bills and pay the rent and keep the wolf away from the door — I have to figure out something. And again, while I was at University of Toronto, there was an ad in the Varsity — a fellow who was setting up a film company to make instructional documentaries. This was out in Whitechurch-Stouffville, and I can remember going out and meeting this fellow. I thought, “Maybe I can make a living making instructional movies,” because in those days there was a market for that kind of film, and film distributors, if they did their job well, they were making reasonable incomes, and the filmmakers providing the material to these people were doing OK. There were several companies in Toronto that had full-time staff making documentaries of a more instructional character, so I thought, “I could do that.” Since the apple never really falls very far from the tree, I could be a teacher in that way rather than in the university. That seemed like a good idea, but I realized I didn’t have any knowledge about how to make a film. As a graduate student at the University of Toronto, I had a certain interest in learning about film. I don’t think I ever wanted to be a filmmaker, but that was the era of cinephilia. Anybody who was interested in contemporary art, contemporary literature, contemporary painting, contemporary culture, would be interested in the work of Jean-Luc Godard and Fellini and the Taviani brothers …

S: Cassavettes …

E: Exactly. Bresson, who was a great passion of mine — I was already very very enthusiastic about Bresson’s films; Antonioni — filmmakers who have continued to interest me right to the present. Anyway, I thought that it might be a good idea to learn a little bit about the craft of film. Handling the materials helps you think about what it is that camera people and directors and editors are doing, how a film gets put together, how meaning gets made in cinema. So, I had gone to take an evening course at Ryerson, and they opened up a program. They were getting ready to become a university, and they offered a fourth-year course, if you will, for students who had graduated from the three-year diploma program, so I thought I would go and do that advanced diploma. They opened that advanced diploma programme as a kind of experimental curriculum to help them form a four-year program ending in a degree. While I was there, they asked me to stay behind and set up the courses in film history and film theory — subjects that I hadn’t studied. I might say, in fairness to Ryerson, there were not film programs at the time. Peter Harcourt was offering a course in film studies at Kingston, and Grahame Petrie at McMaster offered a course in introductory film studies. Joe Medchuk, around the same time, was hired, I think in the architecture school, to give a class in film to people in architecture.

S: Just like today, the art studio program is in architecture at U of T now, too, so nothing changes.

E: [Laughing] Exactly, the circle keeps turning. So, in fairness to Ryerson, there weren’t people, and I was after all interested in poetry, I had read aesthetics, I had a certain interest in critical studies, critical theory, critical analysis, so I think they thought that I might be able teach myself the rudiments of film studies, figure out what a course might have to be, and supplement the existing practical curriculum in filmmaking with film studies courses. Well, the summer before I was to begin teaching, I became anxious — “What am I gonna do in these courses?” — and I was flipping through a filmmakers’ newsletter, which also happened to contain an article by one Stan Brakhage titled “In defense of the amateur,” and I read it with some interest, but what I was most intrigued by was an advertisement: “Summer institute in film studies.” It was to be in New England, that year, in Durham, New Hampshire, and there would be a course in documentary taught be Ricky Leacock, a course in scriptwriting taught be George Bluestone, a class in photography taught by Jerome Liebling — the year before, it had been offered by Diane Arbus. Somehow Ed Emshwiller was involved — I’ve forgotten if he was giving a course or was there as a speaker or whatever it was. And there was a class in teaching film studies, by a chap by the name of Gerald O’Grady. It turned out that Gerald O’Grady had put together the summer institute — that was an O’Grady extension activity. So, Cathy enrolled in the class in teaching film studies; I enrolled in the course in scriptwriting; and my parents loaned me their car for the three weeks of the course. We drove down to New England — many adventures in Boston in getting there, but I’ll let those go — and the classes began. Cathy came back for lunch after the morning of the first session and was talking about Gerry O’Grady and what a wonderful fellow he was, and that he was teaching at Rice University and was giving advice in the high schools and colleges and even public schools in Rice, and that he had a course at Columbia, and that he was also teaching an extension class at NYU, and that his home appointment was at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and that he was on airplanes every day of the week, and so on. And I thought, this guy sounds like an operator. He sounds too ambitious and entrepreneurial to be a genuine scholar. I was kind of sniffy and thought he must be a terribly ambitious entrepreneurial sort, not spending enough hours in libraries and too many hours on planes promoting himself or whatever. But — let that go — Gerry insisted that all of the faculty who were teaching would do a presentation in the evening to the entire group of students — excellent idea as far as I’m concerned. Ricky Leacock would come and give a session on his films to everybody who was involved in the summer institute; Jerome Liebling would talk about his work in documentary films and how photography had led him to documentary filmmaking; and, one evening, Stan Brakhage, who was also teaching there that year, gave a session on his films. I saw the films Western History, Window Water Baby Moving, Door, I can’t remember what else, but certainly those films in that first session, and I knew that this was what I wanted to do with the rest of my life — that this was the new poetry. Of course, I had been aware of McLuhan’s writings, and sat in on classes that McLuhan gave, and went to public talks that McLuhan was giving at the University of Toronto. My brother used to participate in the seminars, and he brought home many, many stories about the wondrous work that — my brother, who worked with Northrop Frye, also brought back tales of what was going on in the science and technology seminar at the coach house. And I looked at this work by Brakhage, and I just said, this is the new poetry. This is electric poetry. This is poetry for our time. This is what I need to be doing.

S: Was this in 1972?

E: Yes. And so convinced was I of that, by the way, that I’d gone down the summer before I had begun teaching, and I had no income whatsoever — we were both living on Cathy’s modest salary — and I told myself I needed a camera, and walked along the corridor at the school, and I saw a sign, “Bolex for sale.” It was a Bolex REX-5 with a 12:120 Angenieux lens, a motor for the camera, a 10mm lens, a Macro Switar, and a 25mm and a 75mm lens, and an array of accessories for the Bolex — all of this for five hundred dollars. Well, that would be five thousand, seven thousand dollars now, but in comparison to what Bolexes were going for at that time, it was an absolute bargain.

S: Then you need to buy film.

E: [Laughing] Yes. And it turned out, the chap demanded cash. He wouldn’t take cheque, he would take any other form of payment; he wanted cash. So, I went over to the administrative office for the summer institute in film studies, and asked Peter Feinstein, who later became Hollis Frampton’s manager, if you will. He then went off and began administering projects in medical research et cetera, but for a time he was deeply involved in experimental film, and Hollis’s manager. So, I walked in — here I am, from Ontario, this is New Hampshire — and I said, “Could you give me five hundred dollars, and I’ll give you a cheque in return?” “Oh sure, no problem.” [Laughing] and he handed me the five hundred dollars and we went out to buy the camera. We had to go to the back woods of New Hampshire, which is really lovely — it really is wild — and this chap had been building himself an A-frame house out in the woods. Very much an Emersonian-Thoreauian sense of things — we have to get back to the land and back to nature. There really was a strong strain of this among certain people in New Hampshire, and I guess he decided that his A-frame was more important to him than the Bolex. He had been at the summer institute the summer before, and he had heard Stan Brakhage speak. [Laughs] And when he heard Brakhage speak he was absolutely converted, and he had to immediately buy himself a camera and start on the path to become an avant-garde filmmaker. Anyway, after this, I began sitting in on Brakhage’s classes on the songs.

S: So, at this point, when you saw Brakhage’s films, you hadn’t seen very many other experimental films.

E: I had seen several works by the Kuchar brothers. I had seen one of the first screenings — not the first, but a very early screening — of Michael Snow’s Wavelength. I was utterly appalled at the response of the audience to it. You’ve heard stories of the reception of Michael Snow’s early films in the early days, and there was jeering and hissing and booing. I was involved in organizing the arts festival at McMaster, and we had brought up programs of experimental film, and we already had enough of a sense of how you could fund bringing up poets and writers — I brought up Allan Ginsburg and Kenneth Rexroth; Susan Sontag came; the Exploding Plastic Inevitable Came, and in fact went to a party in Dundas, Ontario at Peter Rowe’s house with Nico and Gerard Malanga. And shortly after that, McMaster had also brought in one of the very early screenings in Canada of Chelsea Girls. It happened on a day not too unlike this — it was such a trek to get to McMaster for the screening, and there was almost nobody there, because already the snow was two feet high by the time the film was over, and it was almost impossible to get home. Anyway, to fund the arts events, we also arranged programmes of work by the Kuchars — Hold Me When I’m Naked and Sins of the Flesh, and of course we put those in the engineering department’s building, so the engineers would see the posters for Hold Me When I’m Naked. And they flocked to it of course — helped pay the bills — and then they’d leave early. This wasn’t exactly the film that they were expecting to see. [Laughing]

S: So, you were versed already, but it was Brakhage that —

E: Brakhage was missing. We had also met — speaking of trying to learn a little bit about the cinema — Cathy and I also took an extension course that summer in filmmaking, and it was experimental filmmaking, and it was taught by a chap by the name of Henry Zemel, a name that may ring a bell for you or may not. Henry Zemel was a very good friend of Leonard Cohen — in fact, when Leonard was in distress in Nashville, at that time, Henry Zemel had to go down to assuage his anxieties and to talk him into continuing the work that he had gone to Nashville to do — and Henry Zemel had worked at the National Film Board and was friends with Arthur Lipsett. We had already screened work by Arthur Lipsett. I knew of Lipsett’s films by this time — was really quite familiar with them — and then Cathy and I met Lipsett on that occasion. Lipsett films were among the first that I showed to Stan Brakhage when he was exploring Canadian films. The first, of course, was Hart of London, but that was followed very shortly by other work by Jack Chambers and Arthur Lipsett. But there was a confluence of influences at that session in New England. First, encountering the work of Stan Brakhage, seeing this new electric poetry. O’Grady is, of course, utterly McLuhanite in his outlook. He revered Marshall McLuhan; he thought that McLuhan was one of the great theorists of art at the time. He was very deeply impressed by McLuhan’s interest in pedagogy, and the importance of thinking about media in order to understand its potentially baleful effects, and perhaps steering our understanding of altering our nervous system in a way that we would be able to respond more effectively to the new media. And of course, that had been a strain of thinking that I had been exposed to before going, but O’Grady’s incredible passion for this really had an impact on me. And then, finally, after seeing Brakhage’s film that evening, the next day Brakhage was signing copies of the book that he had just released — his first book, The Brakhage Lectures, in the Good Lion Press edition. I don’t know if you remember that …

S: I think so — those are the lectures on Meliès and that sort of thing?

E: Yes. And the first was “Now let me say it to you just as clearly as I can, the search for an art either in the making or appreciation is the most terrifying adventure known to man, for it will threat the soul with terrible death and it will leave the mind moving,” et cetera. [Laughing] Anyway, I of course, after seeing the films, wanted a copy of the Good Lion Press edition of The Brakhage Lectures, and asked him to sign it for me. He was always a very gentlemanly sort, and so, when I went up, “Please Mr. Brakhage, will you sign my book?” he asked me why I had come to the institute and what I was interested in, and I guess I had told him too that the films had had really a great impact on me, and that I was an aspiring poet — I was already a published poet, in fact — and I knew this was the new poetry of our age. So, he said, in signing, “Have you read Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era?” I said no, I hadn’t read it. And he said, “Please, read it. It’s the most important piece of critical writing on poetry that I’ve read in decades.” So, I did. And of course, Hugh Kenner was also a student of Marshall McLuhan. I think Kenner’s dissertation was the second dissertation that McLuhan had supervised. McLuhan introduced Kenner to Ezra Pound on a trip to a conference and so on. So, in a way, that reading of Pound’s verse just re-emphasized for me a new way of thinking about verse, a way of thinking about verse that was rooted in McLuhan’s ideas of the transition from written forms to a return to oral forms in poetry. So, all that came together at once in that first encounter, and really, it’s continued to shape how I think about Stan Brakhage. We’d see each other from time to time. I found ways to invite Stan to come to Toronto and present works. This was in ’74–‘76 — that period of time, right up I guess until around 1981 or ’82. I don’t think I invited him between ’82 and ’86. But, from time to time, I was able to invite Stan to Toronto. He was always very cordial, very gentlemanly, very kind, but it was very clear that he saw me as an academic. He began to read from time to time pieces that I had written, and moreover he had heard of films that I was making, and knew that they were growing longer. Long films, for him, were — despite his having made The Art of Vision — associated with structural films, and structural films, for him, were a moral failure, and I do mean not simply aesthetic, but an aesthetic moral failure.

S: He had to kind of re-construct that idea later as he started to watch films again. But I’ve seen him say that. I even remember telling that story about the fateful visit — he was terrified of having to watch Lamentations, because it was not only long, it was really long, and he was pretty sure he wasn’t going to like it.

E: It was actually at Miami. Until that time, as I say, Stan thought of me as a critic, an intellectual — a dry-as-dust intellectual — who would probably be making very, very derivative work in the structural vein. I remember, he had come up to show The Text of Light, and he saw me and Cathy in the audience at the end of the screening, and he called us over, and he said, “Why don’t you come out to … we’ll go out for coffee together,” and another couple he saw in the audience at the time were Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland, and he invited Michael and Joyce to join Cathy and me and him and Joe Medjuck and Linda Beath, who had decided to distribute The Text of Light, for a coffee. And we went to the Courtyard Café for a coffee — I don’t know if you remember what the Courtyard Café was, but it was pretty prestigious, and the cost of a coffee and a cake was absolutely extraordinary. So of course, you could imagine this of Linda Beath, it was all, as they say, Dutch treat, so Michael and Joyce had to pay for their coffee and cake, and Cathy and I, and we were wondering how we were going to make the bill. Michael Snow looked at the bill and winced and said, “Ah well, easy come, easy go.” But Stan was very — he acknowledged that he knew me, that I was working on experimental film, that I was a critic of experimental film, and he was certainly very gentlemanly, but he thought I was a dry-as-dust academic. And then, we were invited by Bruce Posner, actually, to an even in Miami — Miami Waves I think it was called, if I’m not mistaken. Another piece shown on that occasion, by the way, was a slideshow by one Nan Goldin, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, also shown at that event, and Sandra Davis was there showing Maternal Filigree. It was a lovely, lovely event.

S: And what were you showing?

E: I had one program that was short films and The Art of Worldly Wisdom. We hadn’t really said anything by this time. And then the next day was Illuminated Texts, and I ran into Stan in the washroom, who told me he was looking forward to seeing the film after the previous evening’s, and he was really taken with the previous evening’s work. And then, after Illuminated Texts was over — you recall, I’m sure, how effusive Stan could be when he was impressed with a work that he had seen, and he’d certainly speak up from the audience and ask questions and deliver a discourse on the work.

S: “This is the best lasagna. The platonic essence of lasanganess.”

E: [Laughing] Yes, it was that sort of style.

S: I never felt like he was lying when he said that, by the way.

E: No, no, this was deeply felt passion. And he was capable of being really carried away by work that touched him. And it was evident at the end of the screening that Illuminated Texts had had a great impact on him. I can still remember what it was that he began talking about at the end of the film. First of all, he knew it was on history and technology and nature and so on — he identified those themes in the work — but he also saw in in a contrast — and there is, absolutely is — between geometric forms of construction and natural forms, between biomorphic forms and geometric forms. And of course, he associated geometric forms with anxiety, fear — an attempt to control nature, to impose a grid on nature — while natural forms were the expressions of a vital urge within nature itself. I mean, that’s one of the great themes of Dog Star Man, isn’t it, which is also, in a sense, an extended creation myth repeated over and over. It’s not that the myth begins and we see nature evolving, but it is about the creative force that is running through nature and bringing all that is to be, creating all of the beautiful luminous particulars. So, he was taken by the contrast between geometric forms and natural forms, which of course comes out again in the Telling Time book — there’s one article specifically on that, and then he also alludes to that theme in writing about other works of mine. But it was hilarious about Miami. These were the days in which the Colombian cartel was shipping drugs into the United States through Miami — you know that popular television program. [Laughing]

S: I’ve seen the Brian De Palma film with Al Pacino. [Laughing]

E: Anyway, so he’d describe afterwards how we became friends — and he did tell the story that I think you’ve heard, that when he was invited he looked at the program and he saw, well, they’re going to show the hour-long film and this and that, and the three-hour film — thank goodness they’re showing the eight-hour long film! But behind that story is too — what’s hidden within it … well, not so hidden, but what motivates it of course is a sense that when he’s invited to events and can see other experimental filmmakers’ work, that he was obliged to go and see it and to talk with them about it and so on. If Lamentations had been there, “Oh my god, I’d have had to go to the eight-hour long film, because I feel that’s my obligation to the field.” So that’s something in itself. Anyhow.

S: Before we move on from there, I wonder what he thought of Nan Goldin. I mean, I don’t need to know, but I’m just saying.

E: I don’t think that ever came up with us. I remember going over and taking a look at it and being quite shocked with its explicitness, but of course that’s a kind of social documentation. I think she’s a very, very good photography. I don’t want to be taken as making derogatory comments when I say this about it. But, mostly, it’s social documentation of people at the edges, at the margins of society. It’s a document of a subculture, and that’s a kind of a genre that … I had known Tulsa, Larry Clark’s book, from long before that, and Chelsea Girls and so on. And yes, I think Stan had been living amongst … that documentation of a subculture was a common practice in New York among acquaintances of Stan’s. So, I don’t think he would have seen it as a shocking new work. So, anyway, he’d tell this story of how he saw the program before and then he was so glad that they were only showing the three-hour long film by Bruce Elder and that he wouldn’t have to see the eight-hour long film. So, there we all were — Sandra and Stan and Cathy and me and Bruce Posner — in this swamp in Miami, and bullets are flying over our heads while the movies are being shown. He really did describe it that way as though he we were in the den of thieves, a very dangerous, dangerous place, and here are these small band of people interested in avant-garde art showing their work to one another, and he sees this work and he just falls in love with it. And, in fact, I knew actually, before we had gone to Miami that I’d be seeing Stan again later that year, because I had been asked who I would invite to the Kodak Lectures, which were a series of lectures at Ryerson with really major artists. The funding was very good; we paid a pretty good fee for people to come to the events. Robert Frank came.

S: He did that one at Innis — I mean at the AGO.

E: That’s right. Oh, there were two. The first was actually in the bottom of the library building. There was L72. You’ve been in that building — the same room that Jonas gave his Kodak Lecture in when Stan died.

S: Right. I remember doing it. We collaborated on the Frank. Don allowed us to do that, which was kind of crazy because we only had two hundred seats, and it could have been in Ryerson Theatre or something, easily. He was funny. Remember, here was his lecture, his actual lecture that day. [Long pause] Any questions?

E: [Laughing]

S: And it was great. It was perfect. That was all he had to do.

E: The talk at Ryerson was so — I can remember going out to dinner with him before. He had come partly because he was friends with David Heath, a guy I liked very much.

S: I’ve never met David Heath, but I have the important book.

E: Dialogue with Solitude. And the book that came out of the Art Centre in Kansas … Manifestations, was that it? No. I can’t remember the title of the book. It had something to do with … it’s a play on solitude. Can’t remember the title, but the catalogue is extraordinary, and one began to see from that book — it collected a number of unpublished photographs by David Heath, and David Heath was a really important documenter of the Beat scene in New York City. And yes, Dialogue with Solitude has the wonderful photo of the person reading Howl and another picture of Gregory Corso and so on, but in fact, most of what David was doing while he was in New York City was going to Beat haunts — cafes, readings, lecture series, soapbox sort of events in churches in New York where the Beats were declaring the need for the transformation of society and so on, and David was documenting all of this. Anyhow, we went to dinner, and I have to say it was one of the — unlike Stan … when you went to dinner with Stan — and you’ll remember this — Stan could carry the conversation, talk about poets and painters that he knew, had wonderful anecdotes.

S: Frank would have been kind of depressive …

E: He couldn’t carry it. The conversation just — it didn’t take place. And then, so we left from this dinner, which was very, very awkward, and went over to the L72 for the lecture, and it consisted of: he’d turn and look at the screen, turn back and look at the audience with a puzzled look on his face, look at the slide, look at the audience, again, bewildered, and then he’d look, and he’d say, “I shot this in Wisconsin in nineteen…fifty…three.” Next slide.